New Blog Location

Dear readers Mitch now blogs at the Organized Binder website. Please join him there! Thanks for reading and sharing.

Whenever I get the privilege of speaking to a group of educators I always make a point to ask one simple question, “What are teachers doing from within the classroom that most directly impacts student learning and achievement?” The responses always vary but one classroom strategy is always highlighted: have very clear high classroom expectations (The Doing).

I agree that high expectations are critical in the classroom to help all students achieve. In order to have effective high expectations two questions must be answers: 1. What are the right high expectations? and 2. How do we communicate them to students (ie make the “clear”).

High expectations tend to come in lists that might look something like this:

- Be on time

- Be respectful

- Be prepared

- Bring your materials

- Try your hardest

I’m of the mindset that fewer expectations are better in the classroom. I am also convinced that it is not really the list that is most important, since most are pretty similar. What is paramount is the second question, how do we communicate these to our students?

Most of us include these lists in our syllabi and many teachers post them on the wall of the classroom in a strategic location to maximize exposure. These tactics are fine, maybe even necessary or mandated, but I find that I still need to continually remind my students of my high expectations even though they see the list each day the enter class.

This winter I was training a high school staff on Organized Binder and we were talking about how to use the Kick-Off question on the Lifeline. I had reviewed all the tactics explained in this series, “A Starting Routine can Change Everything” but there were still a few perplexed looks on teachers faces. Then I showed them a video clip of a classroom starting with the Kick-Off. A teacher named Nick sitting in the back said, “Oh! That’s what you mean. Now I get it.” Ever since he has been using the Lifeline as it is intended and seeing amazing results with his students.

A few weeks later I had a chance to chat with Nick and I asked him to explain what seeing the video did in that my demonstration did not. He just simply responded by telling me you showed me what it looked like in the classroom instead of just explaining what it looks like in the classroom.

This is exactly what Organized Binder does for teachers and students. It makes most of the high expectations in the classroom plainly clear. For example, it shows them what it means to be on time (you are in your seat with your binder open to your Lifeline (B page). It shows them how to be organized (Your assignments go in chronological order behind the Table of Contents (Page H). It shows them how to create a tool from which one can learn and practice studying (Kick-Off questions and answers – Page B). To name a few.

I have been thinking about that conversation with Nick and have come to the conclusion that one of the reasons teachers and students are so successful with Organized Binder is they can see exactly what it looks like to use it. In other words, many of the teacher’s high expectations are not just explained and posted in the classroom, they are also experienced. Paulo Freire might explain it by urging teachers to make students increasingly more subjects in their education and less objects in that experience (p. 33 Pedagogy of the Oppressed). Too often students experience education happening to them rather than being an active participant in the process.

What if you took down the list of expectations in your room and instead you went through each one and showed your students what it looked like to accomplish them? If you cannot do this then get rid of that expectation, as it might be either too high or too vague.

Clear high expectations must be shown not explained. For fun try it. Take down the list (if you post one) and come up with a strategy to show your students exactly what it looks like in the classroom to fulfill each expectation. If you try it, let me know how it goes.

Thanks for reading,

Mitch

Bullying in the Classroom Part 2

I AM TIRED OF BULLIES!

I am just sick and tired of people taking advantage of those they perceive as weaker or more vulnerable than they are.

My 2-year-old daughter, who today overcame her fear of climbing up the steps to the “big” slide at the park, was sitting at the top of the slide just about ready to let go when some elementary school-aged kid behind her started kicking her in the back! He obviously wanted a turn on the new slide at Dolores Park and was growing impatient while this 2-year-old sat contemplating the significance of what it would mean to let go. After taking repeated blows to her back, my daughter burst into tears at the top of the slide. My wife quickly scaled the ladder and grabbed her while giving this kid a piece of her mind.

I’m sure I avoided a few months (read: years) in the penitentiary today because my wife was at the park instead of me when this happened. I knew that my daughter would recover from her experience—and after crying for a half an hour in my wife’s arms, she did. When I asked her about it over dinner tonight she recapped it by saying, “Daddy, that boy is NOT nice!”

If I could just invent a time machine!

In my mind I said, “You are right, he is NOT nice and that is NOT okay!” But with every fiber in my being I wanted to be there to defend my kid and teach this bully a lesson.

When did bullying become okay?

I am so sick and tired of society’s mantra that being bullied is just a part of life. No, being bullying is NOT just part of life! It does NOT make people stronger! It is NOT a rite of passage! It is NOT a part of growing up! It is WRONG and unacceptable!

Bullying should never be a part of life, and most certainly not a part of the classroom.

I was bullied in middle school, and I never told my parents or friends about it. In fact, I’m not sure I’ve mentioned it to anyone besides my wife since I was in 7th grade. I recall walking in fear between every class down the hallways of Barrett Middle School. For some reason unknown to me, I had become the target of a group of boys at school. I can still picture the faces of these boys as they approached me each day in the hallway. Their tactic was to knock all the books and binders out of my hands (get a backpack, kid), then stop everyone in the hallway and point and laugh at me. I realize this is not the worst it can get, but I can still remember that feeling I had nearly 30 years ago like it was yesterday. Each day I would wonder if I would see these boys, and cross my fingers just hoping they would not notice me. I never had such luck.

Bullying changes you, and not for the better. Feeling powerless in an unsafe environment changes you. And although being bullied in my youth was terrible, I find myself fortunate to have experienced it because I am now better equipped to help students who are being bullied, and to help create safe classroom environments.

After writing the previous post entitled Bullying in the Classroom, I realized I should have titled that entry “Bullying IN the Classroom.” I wrote that post as I thought about the talk I was asked to give at the CLM Summit of School Climate and Safety. While driving to the Summit and reflecting on my talk and blog post, I realized a gross oversight: Bullying IN the classroom is entirely different and more detrimental than bullying on the playground or in the hallways. Each is abusive and wrong, and the primary charge of all teachers is to create environments where such abuse is not possible.

The fundamental difference between bullying in the hallway and bullying in the classroom is the victim’s ability to escape. If a student is being bullied on the playground they can theoretically remove themselves from the abuse by walking toward or to a person of safety who is always within visual contact, or at least to a safe location on campus. My daughter, who was sobbing in fear at the top of the slide while being kicked in the back, had the advantage of a nearby person of safety: her mom, who came to her rescue. However, such escape is not possible in the classroom if there are spaces left undefined. If a student is being bullied in the gray areas of the lesson, their assailants can hold them captive. They cannot escape because the abuse goes unnoticed by the teacher.

As a reminder, gray areas are unsafe for students!

To be clear, when you have lesson plans that include undefined time, you create space for bullies to attack their victims.

I don’t have much more to say than this: please use a system or create a predictable classroom environment that does not allow for undefined space, because the undefined spaces are the scariest times at school for some of your students.

The charge of all educators is to climb to the top of that slide and defend your student who is being kicked. For the sake of all of your students, paint the gray areas in your lessons black and white!

Thanks for reading and sharing,

Mitch

Bullying in the Classroom

Earlier this week just after my 4th period class, a student (we will call her Ana) entered the room in tears. She walked over to the teacher with whom I share the classroom and they began chatting. Soon after, she began to cry harder and I overheard her say, “but mister, I don’t want to go to that class!” She went on to explain that she was being bullied and made fun of during her 5th period class.

Ana would be described as a happy kid. She is one of those children that has a positive energy or glow that attracts others. I often see her during passing periods in the hall or at lunch with her friends laughing and talking while they eat. My point is that Ana is not scared to be at school during passing periods or lunch, but her 5th period class is a different story.

“Bullying is often mistakenly viewed as a narrow range of antisocial behavior confined to elementary school recess yards.” (Bullying in School – USDJ Report)

As quoted in this U.S. Department of Justice report, bullying at school is commonly thought to occur during the time spent outside of class: the playground during lunch or recess, the hallways during passing period, or any place on campus outside of a classroom, before or after school. The school where I teach has made a conscious effort to create a safe school environment by hiring additional hall monitors, installing cameras, and supporting clubs that meet during lunch and that are inclusive of all students. In the classroom, bullying is addressed through creative lesson plans and by positive public displays, like decorating the walls of the classroom with community posters.

These are critical steps all schools should take to eradicate bullying and create safe learning environments. However, these efforts alone are insufficient, as evidenced by Ana’s experience at my school. The problem is that very little attention seems to be paid to the gray areas in the classroom. I wrote previously about gray areas in the classroom and that, unless the teacher paints the gray areas black and white, they will inhibit teaching and learning. Gray areas in the classroom are defined as times in which teachers are not teaching and students are not engaged in some type of directed activity. They also mark the times when our students for whom English is a second language and students with special learning needs get lost.

It is definitively within these gray areas that bullying occurs in the classroom. And because of the previously mentioned steps schools are taking to eradicate bullying, I would argue that most bullying on a school day actually occurs during this gray area time frame.

When Ana and my colleague finished talking I asked him if there was anything I could do to help. He explained that Ana was being bullied during her 5th period class because the teacher did not have very tight lesson plans (i.e. there was a lot of undefined time in the class period). Interestingly, her 5th period teacher is known as a good teacher on campus. She is loved by all her students and is looked upon as an expert in EL reading strategies. If I had to guess, her laid-back, casual demeanor is transferred to her lesson plans and classroom routines.

Here lies the dichotomy: a student is routinely bullied in the classroom of a teacher who is widely loved and respected. It would make more sense to me if bullying occurs in the classroom of a checked-out teacher who does little in the way of lesson planning and even less to connect with his students. But in Ana’s 5th period classroom which is led by a teacher who cares, how could this be happening?

It is happening because the gray areas are not painted black and white in this classroom. Ill-intentioned students are left unchecked in this “in-between time” that may last a few seconds or as long as minutes. While this may appear to be a short moment for students to chat while a good-intentioned teacher gets ready for the next part of the lesson, it is unimaginably scary for students like Ana. When a student is struggling to preserve his or her safety, or they are preoccupied with whether or not they are going to be bullied, they are less able to learn.

Deborah Meier says it this way, “Schools that work are safe. We know that infants require safety to thrive, but so do school-age kids. The more time that must be devoted to protecting oneself from bodily or mental harm – from peers or authorities – the less energy there is left to devote to other tasks. Creating safety for kids with a diversity of histories and goals means more than just making them physically safe – it includes helping them to feel safe from ridicule and embarrassment.” (In Schools We Trust)

To make our schools safe for all learners we must eliminate the gray areas in our classrooms. How do teachers do this? What does a classroom look like when free of gray areas? As repeated like a mantra throughout this blog, one way to accomplish this change is to implement Organized Binder. Positive results from implementing this system: teachers gain a starting routine that is clear, achievable, and one that creates an academic setting within seconds, not minutes. They establish systems that help students learn to organize their assignments and handouts in class so that when they transition to another activity, the time it takes to do so is greatly reduced (Note: I have only written about the Kick-Off Question on the Lifeline in Organized Binder. In time I will get to page H: Table of Contents). These classrooms also carry out a precise ending routine, preventing students from gathering in groups by the classroom door (posts on the Lifeline’s Learning Log are coming soon).

Whether or not you choose to implement Organized Binder, for the sake of all the learners in your classroom please paint your gray areas black and white. Students in Ana’s situation could very well exist in every school in the country. To help them feel safe and to achieve, we must act now! I compare bullying in the classroom to the relationship between oppressors and the oppressed. In light of this I turn to Freire for inspiration, “Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.” (Pedagogy of the Oppressed)

Thanks for reading and sharing,

Mitch

“You always pushed me to my fullest and showed me how sweet the end result of hard work in class feels like. I got my first A of high school in your class and found my calling in life; coming from where I came from finding a calling in life isn’t easy. I appreciate every thing you’ve done for me…”

I want to address the concept of creating a safe classroom.

If we are going to engage students, we must provide a classroom environment that is safe. Within that safe space, students find courage to take the steps (risks, for many students) needed to start experiencing academic success. Once students begin to achieve positive results we have the opportunity to prove to them that they can be scholars (i.e. graduate from high school, go to college, or find a professional goal or calling in life).

If you agree with this line of thinking then you’re already aware that one of the foundations of student success is a safe classroom. But what does a safe classroom actually look like?

I ended my last post by saying “I believe that when our classroom routines are dependable, we become dependable adults in students’ lives. They know what to expect from us and our class each and every day.” When we establish our dependability as teachers and adults we simultaneously begin the work of creating a safe classroom environment.

The quote above is an excerpt from an email I received last week from a former student. When Estevan, now a graduating senior, entered my classroom his sophomore year he had very few credits, was gang-involved, had just been released from juvenile hall, and was full of hostility. If I was to get through to Estevan, he desperately needed to experience academic success as soon as possible and he was not going to do so without being in a safe classroom.

As the result of a tough childhood Estevan often took issue with authority; he was one of those students that emotionally shut down (or blew up) when he found himself in a classroom that he felt was unfair or overly authoritarian. So I had to find a balance with him: a space that combined clear classroom routines with accountability for engaging in them. By doing so, I am convinced I subtly communicated to him that I believed in him and his ability; that I believed he could succeed. If I had allowed Estevan a modicum of slack because he was transitioning from jail I would have alienated him from the classroom community and, as a result, increased the likelihood of his failure.

So, what does an unsafe classroom look like? It’s an environment where students are not at ease, are unsure of how the class works, are worried for their personal safety, are worried about failing, do not understand the content, are worried about fitting in, or don’t speak the language well, to name a few.

Now envision a classroom with a clear starting routine that is challenging, yet easy to do (i.e. students are successful the moment the bell rings); that offers the teacher a moment to authentically re-teach and clear up student misconceptions; that all students participate in together, at the same moment; where what is projected on the board looks exactly like what students have in front of them; and that takes place in a quiet setting. With just this one routine we remediate many of the things that create an unsafe classroom for students.

A safe classroom is one in which the teacher has “painted the gray areas black and white”. All students can predict what is going to happen at just about every moment—in particular, at the beginning of class. In order for this to take place we have to establish routines, or rituals, that are clear, equitable, and tangible to students. If we utilize such routines then we create a class that students find dependable because they know what to expect. If our classroom environment embodies these characteristics, then we actually become a dependable adult in students’ lives because our classroom and the experience students have in that space is a projection of ourselves as teachers and humans.

Ultimately, a safe classroom environment is predicated on student predictability and teacher dependability and both of these require consistent classroom routines in order to be made possible.

Estevan finished his email to me last week with, “I did it Mr. Weathers! I Just got my acceptance letter for Notre Fame de Namur University!!! And I am getting a $36,000 academic scholarship! Finally my hard work is paying off just like you said it would 2 years ago. If it weren’t for you pushing me that extra mile I would have never made it. Thank you for everything Mr. Weathers!”

Thanks for reading and sharing,

Mitch

A Starting Routine can Change Everything Part 11: What Teachers Believe about Students’ Ability Influences Student Outcomes

I wanted to get this post published today, January 1, 2012, to start the new year off on the right foot. I would like to thank my wife for continually encouraging me to write, it gets tough to blog once the school year begins! I would also like to thank my good friend Dane Sanders for the not so gentle push he gave this last spring to get me to start this blog. I hope you enjoyed the posts in 2011 and those to come in 2012. Here is to a great year everyone!

My past few posts have been just as much about venting as they’ve been about suggestions on disrupting education to make it work. Warning: the venting is continued here.

Last week I visited a continuation school that had implemented The Organized Binder at the start of this school year. A significant number of the students at this school require special education classes, and many had recently been incarcerated. As I talked with the teachers, it became very clear that there were two types of teachers in the room: those who believed in their students’ ability to achieve, and those who did not. Not one landed between these polarities. One particular teacher, whom I’ll call Linda, is one of the most pessimistic teachers I have met. If one of her colleagues shared a student or class success she would immediately reply with, “Oh, my students could never do that” or “these kids just can’t do that.” She had a rebuttal for every positive thing said about the students.

Another teacher, Amy, shared how her students were now arriving on time to class, staying organized, doing better on assessments and exams, acting more appropriately in class, and experiencing academic success—a first, for some of these students. Amy showed me a few of her students’ binders, which were perfectly organized. Most people would probably not assume that this shining example came from a continuation school whose student demographic is largely special education.

What is interesting, or troubling (read: annoying), about this situation is that Linda and Amy share many of the same students, and certainly the same student demographic. In Amy’s class these students are achieving and making significant academic gains, while in Linda’s class they are failing miserably. Amy credits The Organized Binder for the change in her class and students; Linda implemented, albeit poorly (“because these kids can’t do it”), the same system but experienced much weaker results.

Why were the same students with the same tools successful in one class but not another? As I thought about this over the past few days I noted that much of Linda’s and Amy’s reality is the same: both have the same students and/or student demographic, both have a full-time aide in the room, both teach multiple subjects, both have their own rooms…I could go on. The one difference I did identify, however, had reared its ugly head in our discussion: their confidence in their students’ ability to achieve.

I quoted this excerpt from Marazano in a previous post, but it is worth reading again:

“A teacher’s beliefs about students’ chances of success in school influence the teacher’s actions with students, which in turn influence students’ achievement. If the teacher believes students can succeed, she tends to behave in ways that help them succeed. If the teacher believes that students cannot succeed, she unwittingly tends to behave in ways that subvert student success or at least do not facilitate student success. This is perhaps one of the most powerful hidden dynamics of teaching because it is typically an unconscious activity.”

It is quite simple—what you believe about a student can influence, perhaps even determine, whether or not they succeed academically. If the teacher is convinced a student cannot succeed, then that student will most likely not succeed. Teachers have to believe in their students’ ability to achieve even if it flies in the face of logic and reason! It is our job to help students find academic success before we teach content.

How do teachers get to a place where they don’t believe in their students’ ability? When does that happen? Why was Linda so convinced that her students could not achieve? I am certain the answer lies in the “hidden curriculum,” or what I call the “doing” in a classroom. Let me explain by relaying a story I heard on NPR this morning.

They reported on a man who gives unique guitar lessons known as “call and response” to young aspiring musicians. Using this method, which teaches through sound alone, the instructor calls out a note or chord and plays it, and the students respond by playing the same note or chord back to the instructor. In time, students learn by hearing and not just through traditional methods like reading music and playing scales. During the radio interview the students are heard in the background trying to follow along with the instructor. One student in particular stood out to me because his or her guitar was so terribly out of tune and dissonant—it was like listening to a bad high school band playing the national anthem at a basketball game.

My first thought was this: how could this student learn anything if the teacher’s D chord sounds completely different than his or her own D chord? Surely that must be confusing for the student. How can one teach a student to play the guitar using “call and response” if the student’s guitar is out of tune?

The same is true for the classroom. Consider the guitar as the “doing” in the classroom and the notes and chords, or the music, as the “content”. Unless we first tune the instrument we cannot play the correct notes and chords to make harmonious music. Too often, teachers try to teach the content without first teaching students how to be students. This is problematic because we expect students to just innately “play music,” but when they fall short of our expectations we begin to internalize beliefs about their ability to achieve—and our beliefs in turn influence, or even determine, their ability to achieve (reread Marazano quote). This is a vicious cycle.

Think of it this way: letters make words, words make sentences, sentences make paragraphs, and paragraphs make essays. Teachers would never expect a student to write an essay before learning words, sentences, paragraphs, and their interplay. Why then do we expect this with content?

Is this what happened to Linda? Did she expect her students to “play music” to soon in the school year? Did her students therefore fall short of her expectations? Did she then form a negative opinion about their ability to achieve? I believe so.

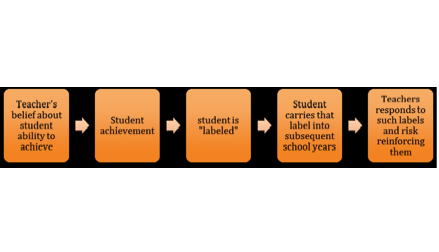

Tragically, this can be compounded year to year, ultimately defining a student’s academic experience. What a student’s previous teachers believed about him strongly influenced how successful the student was that year in school. If the student was not successful, he now risks being labeled as an “underperformer,” “underachiever,” etc. If he was successful, he was likely labeled “student” or “academic,” etc. If these labels stick, students (and their CUM folders) will then carry those labels into the next school year, might be reinforced by their new teachers.

In a flowchart it might look something like this:

Is this fair? Linda, more than any other factor in her classroom, was the reason students were failing. Her students were destined to fail the moment they walked into her class each day. The heartbreak is that Linda’s and Amy’s students carried their negative labels even before they were enrolled in this school. These students, possibly more than any other, need teachers to believe in them! My experience has been that when students spend their time in classrooms where their negative labels are reinforced, as in Linda’s class, they act accordingly and ultimately fail.

Is this fair? Linda, more than any other factor in her classroom, was the reason students were failing. Her students were destined to fail the moment they walked into her class each day. The heartbreak is that Linda’s and Amy’s students carried their negative labels even before they were enrolled in this school. These students, possibly more than any other, need teachers to believe in them! My experience has been that when students spend their time in classrooms where their negative labels are reinforced, as in Linda’s class, they act accordingly and ultimately fail.

When educators teach the hidden curriculum first, students will experience success and begin to see themselves as students/scholars. However, it is even more important for teachers to first visualize their students succeeding so they can begin believing in their students’ ability to achieve.

If you are struggling to teach the hidden curium I suggest that you begin by implementing a simple daily starting routine that immediately sets an academic tone in the classroom and allows students to succeed. Once students begin succeeding, it is more likely that not only will their teachers see them as scholars but that they will also see themselves as scholars. After this you can continue teaching others parts of the hidden curricula that will help your students succeed.

When teachers believe their students can succeed it is much more likely that they will succeed!

Thank you for reading and sharing,

Mitch

A few weeks ago during a talk I was giving to a school, I was drawn into a heated discussion with a veteran high school teacher. During my talk I proposed that starting class with a quiz does one of two things: it either makes the students who know the answer feel good about themselves, or it makes the students who don’t know the answer feel bad about themselves.

I explained that if his student demographic was at all similar to mine, the last thing we’d want to do is alienate the struggling students the moment the bell rings. If we did, we would be far more likely to have classroom management issues throughout the class period. Furthermore, starting class with a quiz would do nothing to inform our instruction that day, that moment.

When I finished my rationale this teacher quickly raised his hand. He explained that he gave homework every night and had a quiz the next day to test mastery. I inquired about the issue of students who did not attain mastery on their homework, and who therefore seemed predestined to fail the quiz. This teacher responded that the threat of a quiz the next day incited motivation in his students to do their homework, and in doing their homework, the students gained mastery. When asked how he assessed whether or not the students had mastery, he answered, “the quiz.” I pointed out that his routine was setting kids up for failure. We clearly were having a bit of a communication breakdown…or standoff.

Trying to gently probe a bit further, I asked about the success rates of his students on the daily quiz. I was not intending to set this teacher up but I knew the students at the school were failing miserably, particularly in his discipline. He acknowledged the poor results, but insisted it was because the students were not doing their homework and that the students were lazy. Whether I was right or not, and whether it was the students’ fault or not, one thing was clear: what this teacher was doing was not working.

After our banter went back and forth for a little while, we politely agreed to disagree.

If you teach at a school that serves a historically under-served population, failure is the last thing your students need to experience in the classroom the minute that bell rings. If you want to give a quiz, do so later in the period once you have had a chance to clear up misconceptions and re-teach content from the previous class. Give students a few chances at success before they have the chance to fail. Pack as many celebrated victories into the first two minutes of class as humanly possible!

These student-successes must be “celebrated;” if successes are not celebrated—or noticed—by you, whether publicly or privately, then for the students they cease to exist. It is akin to the “tree falling in the forest” riddle: if no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound? If no one acknowledges the success, did it happen?

I don’t know if this will convince you to start your class with anything other than a quiz, but I hope it does. Implementing a starting routine that is clear, easy to understand, and one in which students can succeed will effect positive change in your classroom and in student mastery. Ensure that this starting routine exposes any misconceptions the students may have regarding the previous day’s lesson. If you need suggestions, try using the Kick-Off question on The Organized Binder’s Lifeline (page B). Just try beginning with something other than a quiz for a week or two and see what happens.

Give your students the chance to succeed before you give them the chance to fail.

Thanks for reading and sharing,

Mitch

A Starting Routine Can Change Everything Part 9: Be Dependable!

I am on my way to my English class during my senior year of high school. The classroom is at the back of the campus and the walk to that class each day is a long one for me. I hate going to English class! I am slightly dyslexic, a poor speller with nearly indiscernible handwriting, and I have a morbid fear of reading aloud. I get to class early each day and pick a seat in the back of the classroom, slump down in my chair, and pray the teacher won’t call on me.

That is a true story, about a real student. And that student was me. For many students the classroom is not a comfortable space. If a student is anxious, confused, or in some fashion not at ease, she is less likely to learn and more likely to act out in an inappropriate way as a response to that uneasiness. The sooner these students are comfortable in a classroom and the sooner they are a part of the classroom community, the more time the teacher and the students will have to engage in the teaching/learning experience.

What could my English teacher have done to ease my anxiety? It is true that he could not quickly eliminate the academic issues I brought to class. However, the more he worked to decrease my unease the more likely I was to engage in class and therefore to begin making gains in overcoming these issues. Many of the barriers to student success are rooted in the students’ beliefs that they cannot succeed academically. I walked to English class every day convinced I could not succeed, that I was not part of the class.

Ironically, what a teacher believes about her students can strongly influence how a student performs in class and can ultimately influence what students believe about themselves. From out of the beliefs that a teacher has of his students evolves his classroom structures and routines. And it is in our routines (what I call rituals) that students find the traction to make academic gains—it is not in the content. Doug Lemov in Teach Like a Champion says it this way,

“One of the biggest ironies…is that many of the tools likely to yield the strongest classroom results remain essentially beneath the notice of our theories and theorists in education. Consider one unmistakable driver of students’ achievement: Carefully built and practiced routines…”

If my English teacher would have had a simple and achievable starting routine, for example, that he employed everyday in the same fashion then his classroom would have been a place that was less alienating for me. Rather than walking to his class with a growing sense of apprehension I would have walked with a bit of confidence because even though I was not the strongest English student, I would have been a part of the class from the moment the bell rang instead of hiding in the back corner hoping I would go unnoticed.

If we have a starting routine that students can predict and be successful in, then we draw them into their education in a way that content alone will never achieve. Paulo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed said it this way,

“…by making it possible for people to enter the historical process as responsible Subjects (subjects denotes those who know and act, in contrast to objects, which are known or acted upon)…enrolls them in the search for self-affirmation…”

If our starting routine is dependable and the student can enter our class and immediately experience some type of success, then we make them subjects in their education. This is a powerful shift for many students because most of their academic experience has been as an object in their education. Meaning, we want students to know they belong and actively participate the moment they enter class rather than sitting with idle minds being talked at instead of engaging the material.

I watched yesterday while Jesse, a newly immigrated EL student in my 3rd period class with very low English proficiency, entered my classroom. The seating chart was designed so that Jesse sits next to bilingual students and can ask questions of her Spanish-speaking peers as needed; however, I was not convinced this would be enough to make her feel comfortable in my classroom (and I want her to be as comfortable as possible so she will be more likely to learn). But what I observed was that Jesse entered class, picked up her Lifeline, and sat in her seat with her binder open waiting for class to begin. Jesse actually looked just like every other student in the class and therefore she, in that moment, was a student! When the bell rang I revealed the Kick-Off question and she, together with the rest of class, wrote the question and attempted to answer it before we all went over the correct answer together.

My hope is that Jesse’s walk to my science class each day is not plagued with feelings of apprehension or unease as was my walk to English, but evokes a feeling of confidence: confidence not because she knows all the content, or even comprehends all of what is being taught, but because she is part of our classroom community as the result of the dependable routines!

I believe that when our classroom routines are dependable, we become dependable adults in our students’ lives. They know what to expect from us and our class each and every day. Don’t underestimate the impact of this on your students’ academic aptitude, because you may just be the only dependable adult they interact with that day, or that week. Who knows—you might even be the only dependable adult in their life.

To help your students succeed, employ a simple starting routine in which students can be successful—and continue using it every single day of the year!

Thanks for reading and sharing,

Mitch

A nominated edtech blog!

I have mentioned this before and I am saying it again, there is no better place than JackCWest to stay in to loop with the most current edtech innovations and start-ups that have meaningful impact on what we do the classroom!

I am joining a host of other bloggers, educators, and edtech’ers in nominating Jack West for the “Best Edtech / Resource Sharing Blog” and the “Best Teacher Blog”.

If you want to be effective in the classroom subscribe to Jack’s blog. What he posts is the future of education!

Thanks for reading and sharing,

Mitch